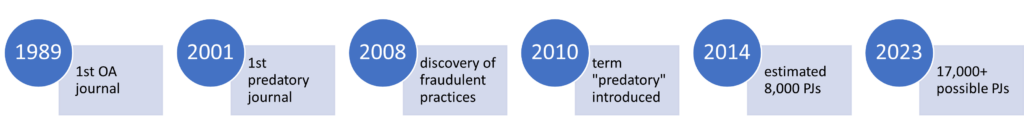

Once, over at the Predatory Publishing1 blog, they tried to figure out what the first predatory journal was and they came up with the Journal of Biological Sciences, initially published in 2001. This means from the launch of the first open access journals2 to what is considered the first predatory journal3, it took approximately 12 years. 7 more years followed until discovering fraudulent practices4 among open access publishers, and 2 years later – in 2010 – the now well-known librarian Jeffrey Beall coined the term ‘predatory’5 to describe this practice. Fast forward another 13 years and in Cabells6 we see nearly 18,000 journals listed as being potentially predatory (March 2023), opposite which stand just shy of 19,000 gold OA journals as indexed in DOAJ7 (February 2023). As far as the open access market is concerned, there is a nearly 1:1 ratio. But even set against the estimated number of all of the active academic journals worldwide (which is considered to be somewhat over 40,0008), the ratio now is just a little over 1:2! How did we get here?

For a while, the open access movement has been mainly blamed for the rise of predatory journals. However, by considering the bigger picture and the complex landscape of scholarly communication in which predatory publishing has taken root, the story has changed, and we see more than just one factor. After all, it would be like blaming online banking alone for the practice of phishing or emails for spam. Even when created with the best of intentions, there are consequences to each and every new invention and technological development. If history has taught us anything, it is that there will always be someone else who will exploit these advancements for their own (monetary) gain, leaving the others out to dry. Unfortunately, the field of science is no different, having always been held to a higher standard and ideal, compounding the losses to more than just a monetary loss. So, while, yes, open access did play a role by providing these journals with its business model, to be sure, this has not been the only factor resulting in predatory publishing.

Over the past 50 to 70 years, the market for academic journals has become very profitable, with a hand full of publishers pocketing most of the money. The first big shift in academic publishing was that from print to the online availability of these journals and their content; the second was the open access movement, representing a shift in business dynamics and changing the model from pay-to-read to pay-to-publish.9 The APC-model charges authors or their institutions a fee per article and while this is not the most prevalent one10, predatory publishers made it their business model of choice because it gave them an opportunity to finally get in on the action. By charging the producer of the goods instead of the consumer, they no longer have to worry about supplying and investing in quality. Should we then place blame on the publishers who came up with the APC business model in the first place? Or the libraries and institutions that blindly went along with it, believing open access would solve their financial strains caused by the serial crisis? No.

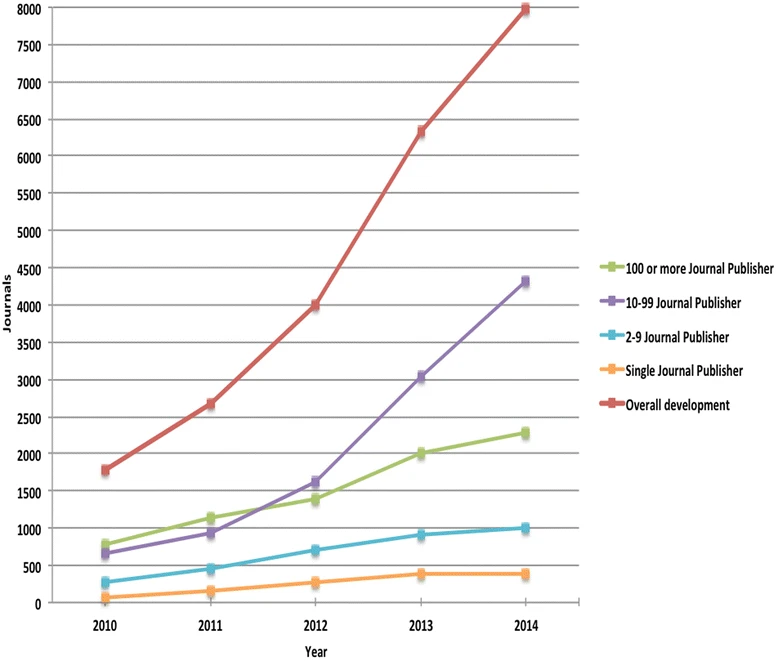

Even if all of these factors play into their hands, they alone do not explain the ‘success’ predatory publishers and journals have experienced in recent years, along with the rise of other similar phenomena that have now spread across other fields of academia ranging from conferences, metrics, identifiers, and paper mills to even creating fake universities and scientists – you name it. You can be fairly sure that fraudulent practices are everywhere. One often cited statistic associated with the development of predatory publishing stems from Shen, C., Björk, BC. ‘Predatory’ open access: a longitudinal study of article volumes and market characteristics. BMC Med 13, 230 (2015)11. This shows an estimated 8,000 predatory journals being published in 2014, with a rapid increase in prior years (see red line in Figure 2).

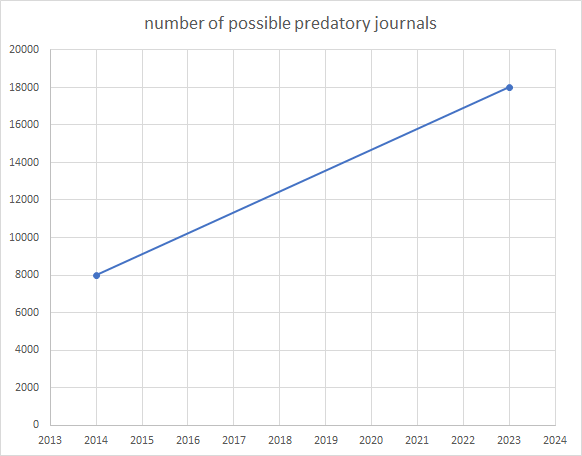

If we look at the gap between this estimate and Cabell’s 2023 figures as mentioned above, and connect these two points on the graph with a straight line, we see a steady growth of approximately 1000 journals a year (see Figure 3). However, the more journals there are, the more sophisticated they become, and the more journals there are in the gray area between trustworthy and definitely fraudulent, the harder it will be to spot them; we will always fall short of counting how many there really are. This begs the question: Are we just seeing the tip of the iceberg? But regardless of the final count, the current number is shocking enough. This brings us back to the question of why these journals have been able to attain the numbers they have.

What has been said so far explains the factors that provided opportunities and a business model for these ‘ventures’, but in order to actually experience any success, these models need people who feed this system: namely researchers, who publish with them. As Clara Ginther stated in the first blog post12, these journals and publishers serve a community that needs their services. Given the modern-day era, where we have gadgets, tools and services available to make our lives easier – and given that human nature is prone to taking the path of least resistance – it is no wonder that people want to take the easy route that predatory journals seem to promise.

In addition to all of the hoops that researchers have to jump through, and the many hats they have to wear these days, above all, researchers have to publish. Indeed, without it, they stand little to no chance of advancing anywhere in academia. As more and more people have the opportunity to attend university and stay on in research, the greater the competition and the need to stand out from among the others. Likewise, those in positions that require making decisions about who to hire, fire or promote, fall into the trap of taking another easy way out: being able to count publications as well as citations and other metrics. While we all know that numbers don’t lie, numbers are objective and can be compared, right? Trying to measure a researcher’s ‘success’ and ‘quality’ by these numbers can be traced back as far as the introduction of the Journal Impact Factor and increased the systemic pressure to publish.

Over the past decades, this has resulted in an enormous rise in the number of publications and subsequently, a rise in the number of new journals bringing in many new players. Given the ever-increasing number of researchers seeking to publish their journal articles, it is no wonder that at some point, scientists knowingly or unknowingly choose to publish in a predatory or other low-quality journal. Predatory publishing then shines a light on the skewed nature of the world of academia and scientific communication, exacerbating the problem even further. While the research assessment system often creates false incentives, encourages the pressure to publish, and continues to feed predatory journals, a silver lining is that the system is currently assessed itself with a goal to not only reform the system but improve it as well13. This process, however, will take some time and whether or not it will even help eliminate these fraudulent actors, or if they will merely adapt to the changing landscape, is debatable.

And what did we do about it?

From the other perspective, let’s explore how predatory publishing was addressed and how it was responded to since Beall’s list and his publications brought predatory journals to our attention. There have been a number of much publicized sting operations in which researchers submitted articles full of mistakes, made false claims, and even submitted nonsense papers to journals in order to see if – and how many – would accept them without question. John Bohannon, for example, did so in 201514. At the same time, a team of Polish researchers even created a fake scientist who applied for – and was accepted to – the editorial boards of several journals15. Two years later, in an article in the New Yorker16, one of her creators stated that this non-existent person was even now organizing conferences and “has taken on a life of her own”.

Another step forward was a successful lawsuit against the publisher OMICS17 between 2016 and 2019, in which the court ruled in favour of the plaintiffs and ordered the publisher to pay damages. Albeit being a positive sign, lawsuits are time consuming, costly and even if one is sure that fraud has occurred, proving it in court is quite another matter. Whether or not lawsuits can actually help in the matter18 is doubtful, seeing as these journals are still active. While these actions, however, are just a drop in the ocean, they have helped raise awareness and showcase these journals’ fraudulent practices and non-existent quality controls, something of which is important in itself.

Going back to 2015, this year also marked the launch of Think.Check.Submit19, an initiative that emerged amid growing discussions and concerns in the field of scholarly communications. The goal was, and still is, to provide scientific authors with tools to help them choose a suitable outlet to publish their research, be it a journal or book. A few years later in 2018, Think.Check.Attend20 was created, offering a similar tool to help researchers determine whether or not a conference they had been invited to is reputable and legitimate. This approach, with checklists and questions, is available in many places, and was designed to get researchers to once again think about the importance of choosing a ‘good home’ to publish their papers. However, once again, many seem to be looking for the path of least resistance. So-called ‘blacklists’, while highly controversial, continue to enjoy popularity – such as the aforementioned ‘Beall’s List’ – which he published on his blog until 2017 until it had to be removed – but which is still used today and continues to live on in other websites.

When looking at the research and writings about the subject of predatory publishing in terms of publication output as indexed in Scopus, an interesting picture emerges. According to these figures, it stayed quiet in that regard, with mostly less than 10 documents a year, until there was surge in 2015 with about 75 publications, and another rapid rise in 2017 that doubled the number to 150 publications. Since then, it has remained at that level, fluctuating between 145 and 160 papers (see Figure 4). This last surge in 2017 also coincides with the first major outcry and attention that predatory publishing was getting in German-speaking Europe. Many entries on universities websites, blogs or news outlets date from this period.

Approximately 35% of the documents in Scopus are categorized as ‘letters’, ‘editorials’, ‘opinions’, or other short communication pieces, with the remaining 65% categorized as ‘articles’, ‘reviews’, ‘conference paper’ and ‘book chapters’. Looking at just the second group, we can see a much more gradual increase (see Figure 5), showing that the big jumps stem from the rapid increase of shorter papers. While these tend to be published in journals that address a very specific group of scientists (mainly medical and nursing professionals), the journals for the longer, more in-depth research and review papers generally focus on scholarly communications, publishing, and librarianship. Similarly, this means we can divide the authors into two categories: one is researchers alerting their peers and making them more aware, and the other is those who study the phenomenon itself. This does not include the communication that takes place outside of academic literature, such as blog posts, news reports, social media posts, etc., all of which seem to be increasing over time and representing another important outlet to get the word out.

When looking at the graphs above, one might argue that the phenomenon of predatory publishing was initially not worth mentioning, or even negligible. Were we still hoping that it was just a glitch in the matrix, a minor nuisance that would one day maybe resolve itself, and crossing our finger to hope for the best? Even today, seeing what we are up against, it seems mind-boggling that some people in academia have never heard of these practices. However, as the number of predatory journals increase, so do the number of publications, initiatives, people, organizations and institutions addressing the topic and seeking to tackle the issue. Meanwhile, a sense of awareness that “something needs to be done” has finally spread to university management and world organizations on a larger scale. UNESCO21, the IAP22, and even our project, AT2OA2 23, are actively addressing the issue, leading us into the next chapter in the history of predatory publishing.

References

1 Blog Predatory Publishing https://predatory-publishing.com/

2 Timeline of the first open access journals: http://oad.simmons.edu/oadwiki/Early_OA_journals

3 https://predatory-publishing.com/what-was-the-first-predatory-journal-who-published-it/

4 https://gunther-eysenbach.blogspot.com/2008/03/black-sheep-among-open-access-journals.html

5 https://www.the-scientist.com/critic-at-large/predatory-publishing-40671

6 https://www2.cabells.com/get-quote at the end of the page. In September 2021 Cabells officially anounced that they reached the mark of 15.000 Journals in their predatory reports: https://blog.cabells.com/2021/09/01/mountain-to-climb/

8 In June 2022 Scopus has 26.038 active journals indexed, that have not been discontinued, including some proceedings.

9 What role these two developments played in allowing predatory publishing to take root has been covered in more detail by Simon Linacre in his recent book: Linacre, S., The Predator Effect (2022), 12ff. DOI 10.3998/mpub.12739277

10 Of the more than 18.000 gold open access journals listed in DOAJ, only a third, around 6.000, charge an APC. In hybrid OA APCs are more common.

11 Shen, C., Björk, BC. ‘Predatory’ open access: a longitudinal study of article volumes and market characteristics. BMC Med 13, 230 (2015). DOI 10.1186/s12916-015-0469-2

12 Ginther, C., Scholarly Communications in Transition (2022) https://in-transition.at/transitions-in-scholarly-communications/

13 The Coalition for Advancing Research Assessment (CoARA) has finalised its Agreement on Reforming Research Assessment in July 2022 with more than 450 signatories by January 2023.

14 Bohannon, J., Who’s Afraid of Peer Review? Science 342, 6154, 60-65 (2013). DOI 10.1126/science.342.6154.60

15 Sorokowski, P., Kulczycki, E., Sorokowska, A. et al. Predatory journals recruit fake editor. Nature 543, 481–483 (2017). DOI 10.1038/543481a

18 Manley, S., On the limitations of recent lawsuits against Sci-Hub, OMICS, ResearchGate, and Georgia State University. Learned Publishing, 32: 375-381 (2019). DOI 10.1002/leap.1254

19 https://thinkchecksubmit.org/

20 https://thinkcheckattend.org/

22 The InterAcademy Partnership has published its report Combatting Predatory Academic Journals and Conferences in May 2022.

Leave a Reply